Yesterday I gave my 9-year-old a bad math task.

I actually knew it was a bad math task, or at least a bad math task for her. It was the most unsurprising thing in the world when it failed, but I still gave it to her.

In my math classes for elementary teachers, some of my favorite moments are when we deconstruct a piece of math that went wrong. I especially love it when students begin to volunteer wrong answers: “I tried this, and I don’t know why it didn’t work,” or “I think this is wrong, but I want to know why it’s wrong.” We learn so much from these mistakes and wrong turns, and I think the same is true of teaching. I learn when I do something that works, but often I learn a lot more when I do something that doesn’t work. So in that spirit, I’m going to share the thing I did with my own child that didn’t work.

My goal was to help her expand her set of strategies for mental arithmetic. She has excellent strategies, by the way (I love sharing them with my students), but there are still times she labors over a calculation when I think there’s probably a more efficient method within her reach. Maybe, I thought, with a little help she could reach those methods.

So. The task. I decided to see if I could teach her a round-to-10-and-adjust strategy. That is, we can take away 9 by first taking away 10, and then adding 1. I threw together a Desmos activity, because kids like computers. (In retrospect, I think I already sensed that I was heading for failure, and I thought, technology! THAT will make her want to do this!) I did not spend very long making the task, which I offer not as an excuse, but…well, okay, maybe I am offering it as an excuse. Here it is, if you want to see it. If you don’t, here’s what you would see if you clicked on the link:

- A page guiding her through the strategy with the problem 13 – 9

- A page where she could draw the strategy on the number line

- A page where she could practice the strategy with other “subtract 9” problems

- Two pages extending the strategy (what if we subtract 8? what about 11?)

- A page of mixed practice

Again, I knew that this was not going to go well. But also, sometimes my students know that a strategy for solving a math problem isn’t going to work and they do it anyway. I think anyone in a problem-solving situation (mathematicians, teachers, parents, or basically anyone) sometimes knows something isn’t going to work, and yet does it anyway, not (always) because we’re irrational, but because trying a bad strategy can still provide us with good information.

I gave the task to my daughter, and as I watched my bad math task land with the thud it deserved, what I found most interesting was not that it didn’t work, but how it didn’t work.

What Went Wrong

The first indication that the task was going to flop came with the first sentence in the activity:

“Oh, it’s 4!” she said almost immediately, definitely not using her fingers.

“How did you do that?” I asked, and she explained her strategy (she knew 13 was 3 away from 10, and 9 was 1 away from 10, so she put together the 3 and the 1), but the point is not her strategy. The point is that:

Problem 1: My task was going to offer her a strategy she didn’t need.

She already knew how to solve 13 – 9, almost without thinking. She didn’t need me to tell her how to solve it.

Still, I pressed on. “Well, let’s continue and see another way you could solve the problem.” She willingly clicked on the buttons on the page that guided her through the subtract-10-then-add-1 strategy, and at the end she nodded. “That makes sense.”

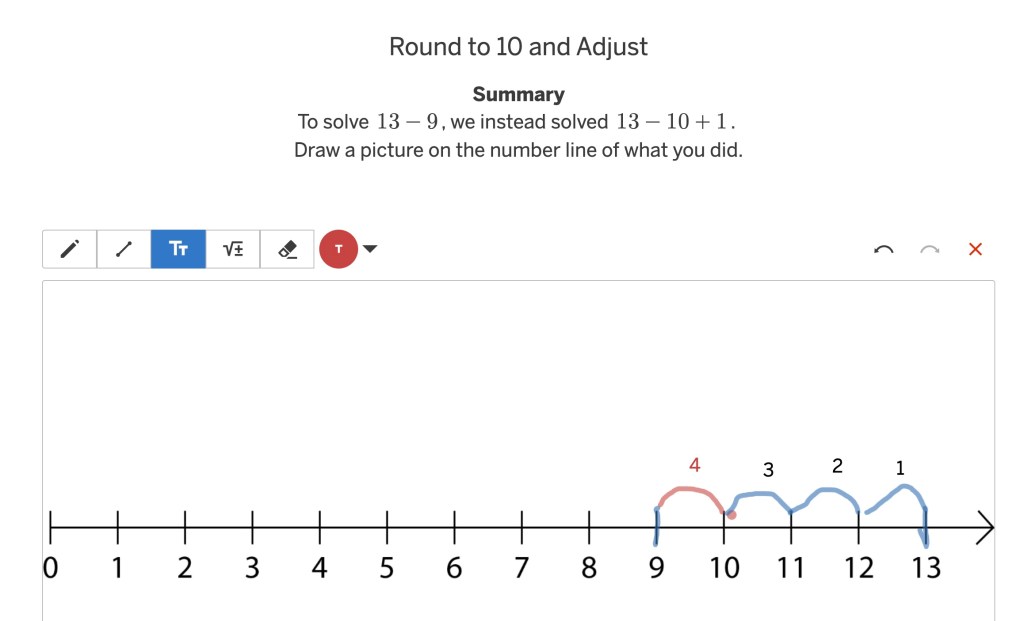

I actually had expected that maybe it wouldn’t make sense to her. Encouraged, I moved on to the next slide, where she got to draw how the strategy worked on the number line. The picture she drew gave me the next indication that the task was not working:

This was a perfect drawing of why 13 – 9 i s the same as 3 + 1. It just wasn’t the way that I was thinking about why 13 – 9 is the same as 3 + 1. I had designed the task around a take-away perspective (13 take away 9); Anya was thinking of subtraction from a difference perspective (the difference between 9 and 13). There was a mismatch between how she was thinking about the problem, and how my task “wanted” her to think about the problem.

Problem 2: There was no reason inherent to the task for her to engage with the intended learning goal.

With her strategy working out just fine for her, she zoomed through most of the next screen of practice problems. Then she got to the last problem on the screen, 25 – 9. Without hesitating, she wrote 26, then looked at me for approval.

“Great!” I said. “You got them all right except for that one.” I pointed to the last problem.

She stared at it for a moment, then deleted her answer and wrote 15.

“Um,” I said.

“14?” she asked. “13?” She started laughing. We both started laughing. She was totally just guessing now.

“Do you remember the strategy?” I asked, trying to salvage the task.

“Oh,” she said, and wrote 14.

“Remember? Subtract 10 and add 1?”

“That’s what I did,” she said. “Subtract 10 is 15. Then add 1.”

It wasn’t that she hadn’t learned the new strategy at all. It was that, while her strategy made sense to her, mine was just a set of steps. When her strategy was challenged by a harder problem, instead of thinking it through, she just tried to do what (she thought) I’d told her to do: subtract 10 (25 – 10 is 15), add 1 (which she interpreted as “subtract one more”).

Problem 3: Handing her a strategy without building understanding encouraged her to let go of her own number sense.

I think the fact that she ultimately landed on 14 was quite telling, because it was so obviously just following steps. She subtracted 10 (25 – 10 is 15), and then “added” 1 more to the amount she was subtracting (take away 1 more is 14). She was following the steps to the letter, but without understanding the intent it was a bit like a game of telephone where the message evolves as it passes from one person to the next.

And I think all of these together imply what was at the root of why the task just did not work:

My task failed to build on what she brought to the table.

I think I could find a better way. Will I? I don’t know. It’s summer break, and getting to do more math with my kids is one of the things I love about the summer, but there are lots of other things we do with our time, and teaching this particular strategy is more a curiosity than a priority for me. Helping her have good experiences with math is much more important than learning and using a particular strategy. But I do think considering what went wrong is worthwhile as I work on preparing lessons for the upcoming semester, and I hope that sharing might be worthwhile to someone else.

If you have a story of a failed task or lesson or teaching moment, in the classroom or with your own kids, I’d be interested in hearing it as well.